Listen to this story using the link below.

Lori Edmo just wanted to find out how her tribe was spending federal COVID-19 relief money. As a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, on the Fort Hall Reservation in southeastern Idaho, she knew her tribal government had received more than $17 million in CARES Act funding as part of the $8 billion in coronavirus relief funds earmarked for tribes nationwide.

Edmo, editor of Sho-Ban News, which is published by the tribe, wanted to keep her readers, primarily among the tribe’s almost 6,000 members, informed about where that money was going — in addition to still more funds through the American Rescue Plan and other mechanisms.

“I’m constantly trying to find out information on how money’s spent,” Edmo said. “We’re a tribal government, and people have a right to know.”

That “right to know,” also called the Right to Information or Freedom of Information, is acknowledged by the United Nations as an essential building block for freedom of expression.

It’s a no-brainer to Edmo, but at times she’s found it “pretty difficult to get information” from the tribal government. Her predicament is familiar among journalists covering Indigenous tribes, the vast majority of which do not have an FOI law on the books.

While the distribution of federal funds is public record, the sovereign tribal governments within the country release information at their own discretion. In the case of COVID relief money, anyone can find out from the federal government how much COVID relief money was distributed to each recipient, including tribes. But unless there’s a tribal law requiring disclosure of how that money is spent, or unless tribal officials are forthcoming with the information even without a law mandating them to release it, there’s no legal recourse for tribal members to demand the disclosure.

Combined with economic and cultural obstacles to a free press, limited access to government information makes journalism about Indigenous issues all the more challenging. But individually and through growing professional networks and initiatives, Native American journalists persevere — in both their reporting and an ongoing campaign to bring Freedom of Information to tribal nations and advance Indigenous press freedom.

In 2020, Edmo said she wrote an editorial that included two sentences saying that she worked in a hostile work environment and that she feared her persistence as a diligent reporter would cost her her job. According to Edmo, she was accused of misconduct and fired by her supervisor, the tribe’s executive director. Edmo said she appealed through a grievance process and was reinstated nearly two months later, but the editorial in question was removed from the Sho-Ban News website, and remains censored. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes public affairs manager declined to comment on a personnel matter.

In an interview at the time with IRW, Edmo spoke about the experience calmly, perhaps because it wasn’t unfamiliar. Edmo had been fired once before, in 2003, following coverage of a controversy within the Fort Hall Business Council.

In the wake of that conflict, with the encouragement of tribal members, Edmo said she temporarily ran an independent publication to keep the news flowing — a rarity in Native American communities, where most tribal media are owned and operated by tribal governments because the population often is too small to support an advertising base that can sustain full-time staff. Edmo’s resourcefulness proved effective: In the following election cycle, the newly elected tribal council reinstated Edmo as editor of Sho-Ban News.

“There’s nothing in our culture that says you can’t ask questions,” she said in an interview. “I just think it’s whoever’s elected to our business council, it’s what their beliefs are.”

Over her 20-year career, she has encountered both receptive government officials and those who wanted to ensure that she did not dig deeper. Edmo points out that the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Constitution and bylaws already provide for civil liberties, and one of them is freedom of the press. There could be additional laws, including an FOI provision, but the existence of laws is no guarantee that they’ll be followed. “It’s up to the individual whether they’re going to uphold their duties.”

Veil of sovereignty

A plethora of lawsuits attempting to pry public information out of local, state and federal government hands proves Edmo’s point. But Shannon Shaw Duty, a citizen of the Osage Nation and editor of the Osage News, values her tribe’s FOI law.

In 2021, the tribal-owned newspaper, based in northeastern Oklahoma, asked Osage Nation officials for the names of those appointed to a committee that was determining how federal COVID relief funds would be distributed among businesses with majority Osage ownership. Their request was denied on the grounds that the committee composition was private, with “no public interest served by releasing the names of the Committee members.”

But the Osage News, citing the tribe’s Open Records Act, sued in tribal court and got the names after reaching a settlement with the tribe’s executive branch.

It was not the paper’s first such win.

In early 2014, a few years after the Osage Open Records Act became law, the tribal congress removed Principal Chief John D. Red Eagle from office after he was found guilty on five counts of violating tribal law. Among them: improperly withholding a contract that should have been disclosed when two newspapers asked for it. The chief was also found guilty of abuse of power, interfering with an investigation, misuse of funds and refusing to uphold tribal law.

Osage News was one of the publications whose request precipitated the charges against the chief. Shaw Duty later said the win was gratifying for the precedent it set, but it left scars.

The journalists involved were considered “troublemakers for quite a while, and it took a couple of years for some of those people to get over it and say hello again,” Shaw Duty said.

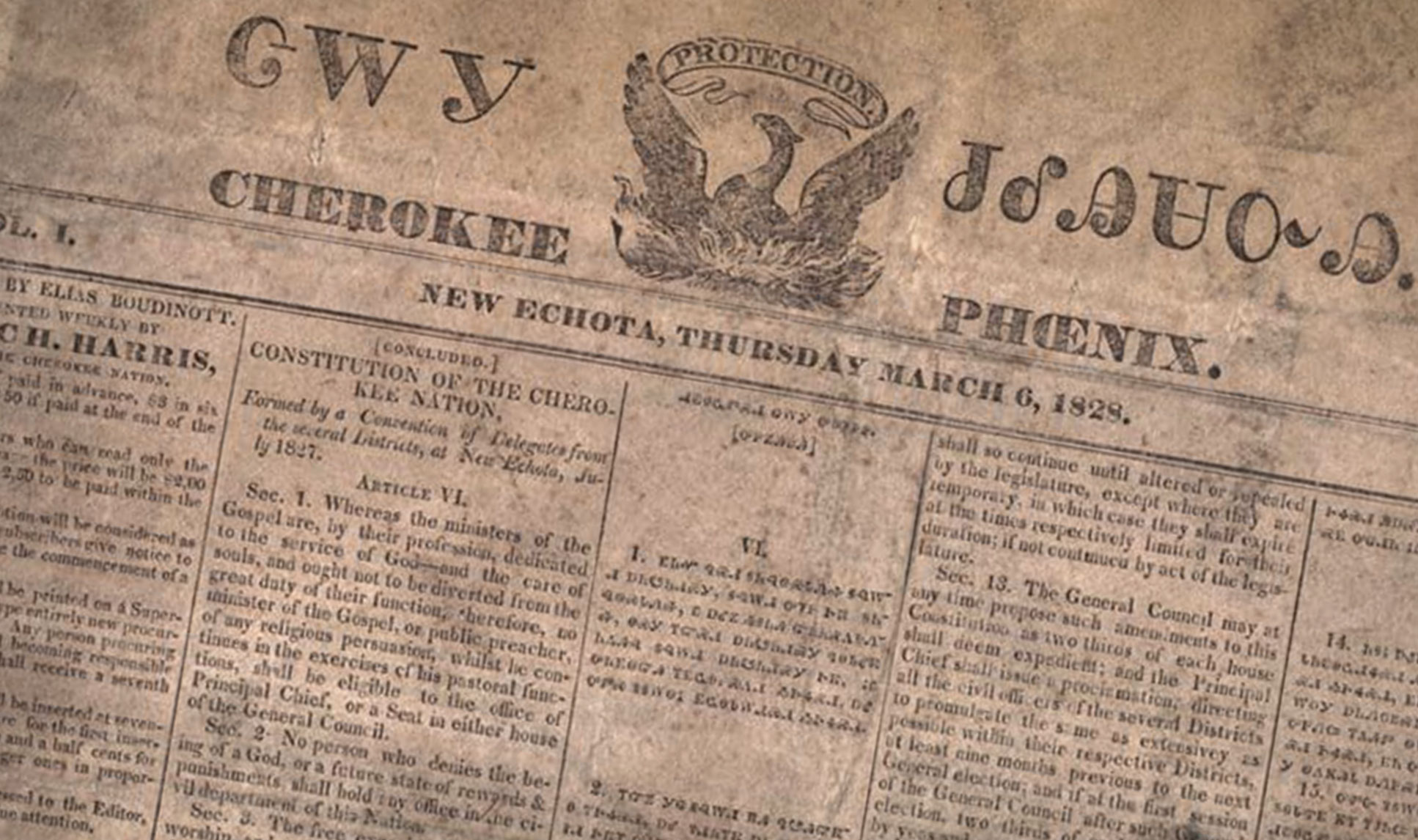

She probably was feeling the effects of what journalist, Indigenous media scholar, consultant and Cherokee Nation citizen Bryan Pollard calls the “dirty laundry effect.” Pollard is an Associated Press project manager, former executive editor of the Cherokee Phoenix and former president of the Native American Journalists Association.

“There certainly is that sentiment from some people — the tribe doesn’t want their dirty laundry exposed, and they see the press as instrumental in doing that, and they don’t like it,” Pollard said. “There has been and continues to be a basic distrust because Indigenous communities have had such poor representation from the media, for so long, that why should they trust the media, frankly? Even when it’s coming from their own people.”

Holding government information close to prevent airing dirty laundry to the outside world — or to protect it from being misinterpreted — is an understandable impulse in that context, Pollard said.

“They can drop the veil of sovereignty so they have a space where they can protect and affirm their political and cultural identity and be self-determined,” Pollard said.

But he said problems arise when tribal government leaders keep their actions hidden from their own constituents. Osage News’ Shaw Duty said that in addition to the social ostracism she faced for challenging tribal leadership, it also hurt her personally to see her chief publicly shamed.

“Even though he is responsible for his actions, it’s still hard to see stuff like that happen, especially for someone that had been so culturally revered for so long,” she said. Shaw Duty counts herself among those who admired him, “until he got to that position and did what he did. And it all turned on its head.”

Still, she doesn’t regret her paper’s position, or the time and emotional investment she put into exercising her newfound right to her tribal government’s information.

“You really, really appreciate it when you’ve never had it,” Shaw Duty said. “Our tribal members never had it. And now that we do, the thought of it being taken away again — that is just unfathomable. That would be a disaster, a travesty.”

Indigenous press freedom

Whether information about tribal governance is obtained through official public-records requests or through the goodwill of government officials, another challenge in Native American communities is the freedom and means to publish or broadcast news when most tribal media is controlled by the very government it’s attempting to cover.

Government ownership of the press is anathema in non-Indigenous America, but it’s ubiquitous for Native American communities. This is due, in part, to historically limited interest in Indigenous issues from mainstream media, even at the local level. When there is outside coverage, low cultural fluency by mainstream journalists often yields inaccurate or incomplete coverage. By necessity, tribes have become their own source of information — and often the only one.

And because economic realities of small and often dispersed readership usually render it difficult for tribal media to finance themselves through advertising or other means, most tribes find that government ownership is their only option.

In practice, this means any government official can walk into a newsroom and say something to the effect of, “I hear you’re looking into XYZ. Don’t.”

Sterling Cosper, a Muscogee Nation citizen and former editor of the tribal newspaper covering his tribe in northeastern Oklahoma, experienced that firsthand.

“My problem is we were called the Muscogee Nation News,” he said of the newspaper, which is now known as Mvskoke News. “That implies it’s impartial, but the structure didn’t reflect that.”

With nearly 90,000 citizens, the Muscogee Nation in northeastern Oklahoma is among the largest Native American tribes. It’s headquartered on a reservation whose lands include much of the greater Tulsa metro area.

In September 2021, a referendum open to all tribal citizens resulted in more than 75 percent support for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing a free and editorially independent press in the Muscogee Nation.

The provision additionally requires the government to fund Mvskoke Media’s editorially independent news operations, thereby bypassing another potential avenue for the Muscogee National Council to undermine the press by defunding it down the road.

That makes Mvskoke News, Osage News, Cherokee Phoenix and the Grand Ronde Tribes’ Smoke Signals apparently the only tribal media outlets — of 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. — that are government funded, yet operate with an editorial independence enshrined in their tribes’ laws. The Navajo Times is one of the few self-funded tribal media operations — a feat arguably achievable only because of the Navajo Nation’s large population and geographical concentration. Other publications that cover Indigenous issues more broadly operate independently, including Indian Country Today, a nonprofit news organization based at Arizona State University.

But Mvskoke Media’s independence was hard-earned.

One morning in the newsroom in 2018, Cosper was heating up a breakfast burrito when an employee rushed into the kitchen and interrupted: “You need to look at this.”

The National Council had called an emergency meeting for the same day with an agenda that included repealing the Muscogee Nation’s Free Press Act.

When it became law in 2015, the Free Press Act had changed everything for the tribe’s journalists. Previously, Cosper said, the outlet operated more as a mouthpiece of the executive department of the government, directly supervised by its National Council. But bolstered by new free press protections, they began flexing their editorial independence, ultimately publishing an exposé of sexual harassment allegations against a council member — someone who Cosper said had championed the original passage of the Free Press Act.

At the emergency meeting in 2018, that council member cast the tie-breaking vote to reverse the progress his tribe had made toward press freedom.

Cosper, unwilling to return to such a paradigm of censorship, quit on the spot. He launched a media campaign to raise awareness — and outrage — about the repeal.

He was keenly aware that raising the public profile about this sudden reversal could trigger the “dirty laundry” effect.

“But now we have self-governance, and we need self-accountability too. This is an exercise in sovereignty, not beating up on ourselves,” Cosper said, adding that they are United Nations “standards of governance. It’s impossible to argue against it in any government.”

His message found receptive ears in the tribe. Not only did the constitutional amendment pass, but also the primary sponsor of the Free Press Act’s repeal in 2018, along with two other council members who had voted for it, were voted out of office.

“It’s a feeling that the war is over. And we can call it a war, not a battle now,” Cosper said. “I think there’s going to be a great pause for actions like this, which gives the new generation a chance to become strong.”

Cosper, now interim executive director of the Native American Journalists Association, said he hopes that the Muscogee constitutional amendment will inspire other tribes to examine the structures under which their tribal media operate, and ultimately ensure them more autonomy.

Solutions

Traditionally, access to information and to tribal leaders was baked into the close-knit nature of how Native Americans lived. Protocols were not written down because Indigenous tribes historically did not use written language. Those who survived colonization and attempts at genocide and then assimilation gradually developed their own writing systems, some adopting English writing systems, and subsequently codified their governmental structures and practices into written constitutions and laws.

Pollard’s 2020 research as a John S. Knight Journalism fellow at Stanford University revealed that most of these laws included provisions for freedoms of speech and of the press. In fact, he found that many of their original constitutions contained stronger language affirming these rights than the current versions, which were rewritten in response to pressure from the U.S. government’s passage of the 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act.

The Act purportedly intended to ensure civil rights protections to Native Americans on tribal lands. However, the newer language on press freedom was akin to the U.S. First Amendment, which in many cases was a weaker protection, stating the government “shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

“That’s actually not a strong freedom, because all it says is, ‘We’re not going to outlaw it.’ It’s not an affirmative protection,” Pollard said. “Those of us who have worked in tribal media and Indigenous journalism know that there are a lot of things you can do to suppress speech and press that don’t involve outlawing it.”

Pollard’s research reveals that work by many Indigenous journalists today to advance press freedom and access to information is not so much promoting a new cause but a matter of restoring these principles to the forefront of their communities.

Pollard said there’s no single solution for establishing effective press freedom and access to information in Native American tribes because there is no one size or shape or culture of Indigenous communities — much less any “typical” form of tribal media. Some reservation tribes, including the Navajo, are populous nations with strong geographical ties. Others, such as the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, in Oregon, have experienced extensive diaspora. Still others are small bands that may not be recognized by the federal government as a tribe.

NAJA’s Red Press Initiative to research tribal media is providing a more granular and nuanced understanding of it, thanks in part to a 2018 survey.

Still, NAJA’s Tribal Media Map illustrates how diffuse this landscape is and how little it is collectively understood or documented. The caption says it all: “This map is not a complete picture. There are many more tribal media outlets who are not NAJA members yet to be placed on this map. Please contact us at contact@naja.com if your tribal media outlet wants to be on the map.”

In the absence of press freedom and FOI laws in most tribes, NAJA’s Indigenous Investigative Collective provides secure mechanisms for whistleblowers to share sensitive documents, data and news tips. The collective also has developed training on baseline security standards and protocols that newsrooms must establish in order to join the group.

Sample FOI and press freedom laws are published on the NAJA website, and the group promotes both through its annual conferences.

Dean Rhodes, editor of the Grand Ronde newspaper Smoke Signals, is one of many non-Indigenous journalists working for tribal media. He underscores the challenge inherent in the mission of getting tribal governments to fund editorially independent news operations.

“It’s a big ask, asking a government to create a watchdog of itself,” Rhodes said. Still, he recalls a joke he made out of a true story at a NAJA conference presentation shortly after the Grand Ronde Free Press Act was established.

“Here are three situations. Which do you think pissed off the most people,” Rhodes asked the crowd. Smoke Signals’ reporting on drug possession? Coverage of two department heads being fired? Or no longer agreeing to take group photos of department staff wearing the same color T-shirt?

They all got it right: The T-shirts.

Smoke Signals has since tackled sensitive subjects, including a tribal elder who embezzled money from the Elders Committee. But their editorial board established criteria for when the news organization would report on criminal activity by tribal members — clear parameters that make every editorial decision to do so defensible.

“It’s coming up on five years, and pretty much everybody’s living by the rules,” Rhodes said.

On the horizon

Edmo said laws or no laws, press freedom, editorial independence and access to information come down to the individuals involved.

“You just have to be a journalist,” she said. “We’re fortunate we have community members, tribal members, and they help us. We find out anyway.”

The fruits of the Muscogee Nation’s recent effort to restore and strengthen its free press will unfold with time. Cosper is confident that the Muscogee people understand the importance of editorial independence after seeing what coverage was like both with and without it.

“It’s great to win if you have to get in a fight,” he said. “But it is not ideal to be fighting with your own people” — especially when your people are already struggling with a dominant society, he said. It’s also less than ideal to be in a prolonged argument with politicians when you’re trying to be a neutral journalist, he conceded.

But if the Muscogee experience benefits the tribe, he hopes his impact won’t end there.

“I hope a signal’s been sent way past our tribe that this isn’t the way to be anymore,” Cosper said. “It never was.”