Two major court rulings in 2010 fundamentally changed the landscape of campaign finance law in the United States. The first was a sharply divided Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which said that corporations and other outside groups could spend unlimited funds on elections. Then, just two months later, a federal appeals court ruling paved the way for new political action committees known as “super PACs.”

The floodgates were opened to unprecedented levels of campaign donations, much of it untraceable.

The decade of elections that followed was by far the most expensive in American history. The cost of midterm elections ballooned from $4.3 billion in 2010 to $5.9 billion in 2018. The cost of presidential elections nearly doubled from $2.9 billion in 2012 to $5.7 billion in 2020.

The proliferation of big money and secret spending also is a consequence of dysfunction and inaction at the government agency founded to regulate campaign finance: the Federal Election Commission. For more than 10 years, the commission has been largely unable to implement basic regulatory changes or investigate high-profile allegations of campaign finance violations. As Democratic Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub wrote to a Congressional committee in May 2019, “the Federal Election Commission has been tethered to the sidelines as super PACs and dark money have exploded across the American political scene.”

The Investigative Reporting Workshop reviewed data on the financing of elections — and the inaction of the FEC — since 2010.

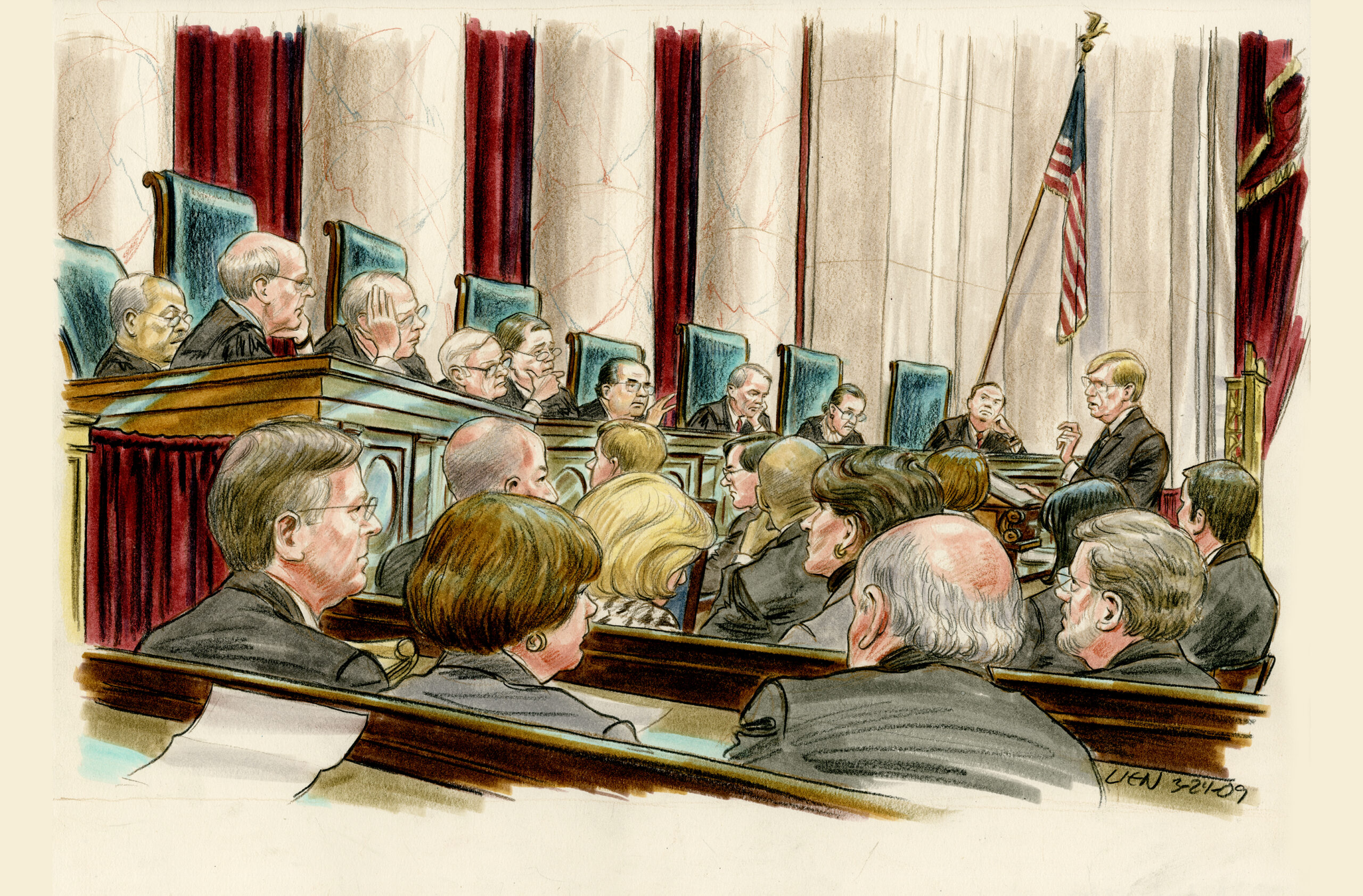

On Jan. 21, 2010, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that prohibiting independent expenditures by corporations and unions violated the First Amendment. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy argued that provisions of the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, which restricted “soft money” and certain forms of electioneering, amounted to government censorship.

“The First Amendment confirms the freedom to think for ourselves,” Kennedy wrote.

The late Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in a dissenting opinion that the Court’s ruling was “a rejection of the common sense of the American people, who have recognized a need to prevent corporations from undermining self-government since the founding.”

President Barack Obama strongly denounced the court’s decision two days later.

“This ruling strikes at our democracy itself,” Obama said in a weekly address, adding, “I can’t think of anything more devastating to the public interest.”

Certain types of nonprofits, such as 501(c)(4)s, whose primary purpose is to benefit the “social welfare,” were now able to spend unlimited money on ads expressly advocating the election or defeat of political candidates, and could avoid the donor disclosure requirements that apply to political action committees.

A ruling in March 2010 by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in Speechnow.org v. FEC struck down federal contribution limits by independent expenditure committees, effectively establishing the super PAC.

In the November 2010 midterm elections, Republicans decisively regained a majority in the House, with a net gain of more than 60 seats, and gained seven seats in the Senate.

Overall, Republican groups outspent Democratic groups by more than $29 million.

More than $6 billion was spent on the 2012 federal election, at the time the most expensive. Also for the first time, spending by outside groups such as super PACs exceeded that of the major political parties. Obama gave his blessing to Priorities USA, a Democratic super PAC founded by former White House aides that spent more than $75 million in the 2012 cycle.

Obama secured reelection against former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney despite Republican groups dedicating more than $400 million in outside spending to oppose the incumbent president. Romney had narrowly fended off primary challenges by former Sen. Rick Santorum and former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, whose campaigns were sustained by donations from wealthy donors, including Sheldon Adelson and Foster Friess. Conservative dark money groups, which do not reveal their donors, outspent their liberal counterparts by about 8-1, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

In the House and Senate elections, Republicans outspent Democrats. The GOP retained a majority in the House but lost control of the Senate.

Overall, Republican groups outspent Democratic groups by more than $500 million.

The 2014 election set a record for the most expensive midterm at $4.2 billion. Republicans retained control of the House and won control of the Senate.

Earlier that year, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission that the 2002 campaign reform act’s two-year aggregate campaign contribution limit was unconstitutional. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., writing for the majority, concluded: “Money in politics may at times seem repugnant to some, but so too does much of what the First Amendment vigorously protects.”

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Stephen Breyer decried the influence of “corruption” in politics. “Where enough money calls the tune, the general public will not be heard,” Breyer wrote.

Overall, Republican groups outspent Democratic groups in 2014 by more than $62 million.

Despite being heavily outspent by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, real estate tycoon Donald J. Trump was elected president in 2016. Overall outside spending in support of Clinton was more than $230 million, compared to $72 million in support of Trump. Super PACs spent more than $1 billion on all federal elections.

Overall, Democratic groups outspent Republican groups by more than $100 million.

At $5.9 billion, the 2018 cycle was, to date, the most expensive midterm election in history. It also marked the first time Democrats benefited more from dark money than Republicans. Liberal dark money groups spent more than $81.7 million, while their conservative counterparts spent $43.3 million. In House races, the Democrats’ spending advantage of $300 million helped them pick up dozens of seats, gaining a majority in the chamber. Republicans retained control of the Senate.

Overall, Democrats outspent Republicans by more than $540 million. President Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court resulted in contentious hearings. The Judicial Crisis Network, a conservative dark money group, spent $3.9 million on television ads supporting Kavanaugh’s nomination, while the liberal dark money group Demand Justice spent $1.1 million on TV ads opposing it.

The 2020 election was the most expensive in history, costing more than $14 billion, more than double the price tag of the 2016 cycle. Democratic groups outspent Republican groups by more than $3 billion. For the first time in history, individual super PACs surpassed $200 million in spending during one election cycle. In another first, dark money surpassed $1 billion, largely benefiting Democrats. Dark money groups such as the Sixteen Thirty Fund and Future Forward USA Action each spent more than $60 million.

Overall, Democrats made gains in the Senate and narrowly maintained a majority in the House.

Biden defeated Trump, who went on to make baseless allegations of large-scale voter fraud. In the eight weeks after the November 2020 election, Trump and the Republican Party raised more than $250 million promoting conspiracy theories about a “rigged” contest.

Much of the campaign spending goes to advertising.

In the 2020 presidential election, more than $1.5 billion was spent on advertising across television, radio and the internet, according to a report by the Wesleyan Media Project and the Center for Responsive Politics. About 65 percent of that spending was from candidates, while outside groups and party committees account for the remaining 35 percent.

The top two super PACs — the Democratic Senate Majority PAC and Republican Senate Leadership Fund — spent a combined $260 million on television and digital advertising. More than 5 million ads aired on television in the 2020 cycle, about double the volume of ads in 2012.

The wealthiest donors are contributing record amounts. A dozen mega donors and their spouses have contributed a combined $3.4 billion to federal candidates and political groups since 2009, accounting for nearly $1 out of every $13 raised, according to a report by the nonprofit Issue One. In the 2020 cycle, the top 100 individual donors to super PACs gave more than $2 billion, accounting for almost 70% of super PAC funds raised that year.

In 2020, the late billionaire Sheldon Adelson topped the list of mega donors at more than $215 million in contributions to Republican super PACs. Also in the top five are former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and hedge fund manager Tom Steyer, who both sought the Democratic nomination for president last year. Both tried unsuccessfully to tap into the economic populism that made Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., a potent force in 2016, despite being members of the “billionaire class” that Sanders rails against.

Even as Bloomberg was busy spending a record $1 billion on his presidential bid, he ironically warned voters that “too much wealth is in too few hands.” Steyer, who spent more than $191 million on his campaign before dropping out after the South Carolina primary, used his farewell speech to decry economic inequality in America, saying that “rich people have been profiting at the expense of everybody else.”

Dark money has been a potent force in state-level politics, as well. A 2016 report by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School found that dark money in six states surged between 2006 and 2014, growing at a faster rate than at the federal level. The report identified several examples of big business spending millions to affect electoral outcomes across the states.

An out-of-state mining company secretly influenced the 2012 Wisconsin state elections by spending almost $3 million to elect a candidate who would implement favorable legislation regarding a proposed iron ore mine.

In Utah, the payday loan industry, seeking protection from consumer rights regulations, worked with a candidate for state attorney general to obscure about $450,000 in donations funneled through dark money groups, helping to secure his 2012 election.

And in Arizona, the parent company of the largest electric utility in the state spent more than $4 million in dark money to influence the 2014 election of two commissioners to the state’s energy regulatory agency.

At the state level, the two parties have been divided on the issue of dark money.

Democratic legislators and governors have passed laws compelling some limited forms of donor disclosure in blue states such as Colorado, Washington and California. Last year, the New Jersey attorney general issued a permanent injunction for a donor disclosure law passed in 2019 after the state was sued by Americans for Prosperity and later by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Since 2020, Republican officials in red states, including South Dakota, Tennessee, Arkansas, West Virginia, Utah and Iowa, have passed laws prohibiting state agencies from disclosing nonprofit donors’ names.

The future of the political race for big money seems unlikely to change unless the two parties can agree on a bipartisan reform. Candidates on both sides of the aisle will criticize big money in politics, even as it helps secure their own election to office. There has been widespread criticism of super PACs from the left and right, but they have become a necessity for candidates who want to win elections. During the last three presidential elections, the winning candidates all denounced super PACs on the campaign trail, only to embrace them later.

Some attempts to eliminate super PACs have raised eyebrows among good-government groups.

On the political left, Harvard Law School professor Lawrence Lessig launched Mayday PAC, a super PAC dedicated to electing candidates who would eliminate super PACs. After most of the candidates lost, The New York Times called Lessig’s effort “quixotic,” and Politico described the $10 million Mayday PAC spent as “money down the drain.”

On the right, Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, has proposed the Super PAC Elimination Act, which would require the disclosure of large donations but would allow unlimited contributions from individuals to campaigns. Campaign finance reformer Fred Wertheimer of Democracy 21 told The Wall Street Journal that Cruz’s idea is “absurd” and that it would “increase the potential for corruption.”

Charles G. Koch, one of the most influential mega donors, has expressed regret for his role in exacerbating the polarization that paralyzes Washington.

Koch and his late brother David founded a vast network of PACs and dark money groups, spending hundreds of millions of dollars funding conservative and Republican groups over the past 10 years. In his 2020 book, “Believe in People: Bottom-Up Solutions for a Top-Down World,” Charles Koch acknowledged that his commitment to partisanship led him and his associates to “head down the wrong road for the better part of a decade.”

“Boy, did we screw up,” Koch wrote, adding, “What a mess!”

In an abrupt shift, Koch now says he and his associates “abandoned partisanship and chose partnership instead.” As he puts it, “We now work with people on the red team, the blue team or no team at all!”

Americans for Prosperity Action, a super PAC that’s part of the Koch network, contributed overwhelmingly to the “red team” in 2020, spending more than $38 million supporting Republican candidates and less than $100,000 supporting Democratic candidates.

In a recent interview with the Investigative Reporting Workshop, former FEC Chair Ann M. Ravel said she was skeptical of the professed altruism of large donors. Ravel, who served as a Democratic commissioner from 2013-2017, pointed to the period after the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Prominent companies, including Walmart, General Electric and Pfizer, took a public stand by suspending donations to the 147 Republican lawmakers who objected to the certification of Biden’s 2020 victory. But, within months, many of the companies backtracked, donating money to congressional Republican PACs rather than to individual legislators.

“Now that they’ve gotten their names published as being good guys, they’re going back to giving money again,” Ravel said. “So, I think people who have that much money, and who give that money, are certainly motivated by the ability to influence high-level officials, and I don’t think that is ever going to change.”

The inside story of the FEC:

- Was campaign finance an issue when George Washington was president?

- What is the FEC?

- The FEC commissioners debate what “deadlocks” even mean

- Who’s in “holdover” status on the FEC today?

- A look at Japan, a democracy that is not as transparent when it comes to campaign finance reporting