SAN DIEGO — Abed Samadi stood frozen as chaos buzzed around him. Bodies darted back and forth. Yells echoed in the air.

But for the sixth-grader who had just moved to El Cajon as a refugee from Afghanistan, this chaos was good. It was fun.

It was a giant game of tag.

A smile spread across his face, and Abed joined his P.E. classmates at Emerald STEAM Magnet Middle School. Dressed in a gray T-shirt and dark green shorts, he blended into the whirling mass of students, their sneakers squeaking across the glossy gym floor.

It was April, and Abed, his parents and four siblings had arrived in San Diego in March — just days before President Donald Trump’s second travel ban was set to take effect. For the kids, school quickly became a source of joy.

“One thing that really impressed me is that when my kids joined school, they were very happy,” said Abed’s father, Hamad Samadi, through a Dari-speaking interpreter. “On vacation they were upset. They said, ‘Why aren’t we going to school?’ This surprised me.”

California now leads all other states in refugee resettlement, according to State Department figures. But San Diego County — which took in the most refugees in the state last fiscal year — has long been a destination for people escaping war or persecution in their home countries.

Since 1975, more than 85,000 refugees have made San Diego County their first home. And though the area’s refugee population has become increasingly diverse over time, one thing remains constant: Many refugee parents wrap their hopes for a new life here in the promise of a quality education for their children.

More than 3,000 refugees resettled in San Diego County during federal fiscal 2016, leading some in the community to question whether area schools — many already operating with limited resources — would be able to deliver on the refugee dream of a quality education for all in America.

As more refugee students enrolled across the county, some campuses found themselves grappling with the unique needs of more newcomers than ever before. Many students spoke no English, some had never sat in a classroom and complex mental health needs were abundant.

“Some of the things they’ve seen or experienced, you cannot even watch in a movie. You have to look away,” said Daniel Nyamangah, a community advocate who works with area high school students.

Though the future of the federal refugee program has been put into question under Trump, last year’s influx of new arrivals to San Diego County — the third highest on record since 1983 — could have a lasting impact on the region’s public schools.

In this special report, we looked at three examples of how San Diego is educating its refugee students, including what challenges remain and what it could mean for the future of the county.

Cajon Valley Union School District: ‘They want the American dream’

On a breezy April morning, clusters of students gathered in the main quad of Emerald STEAM Magnet Middle School in El Cajon. With backpacks slung over their shoulders and remnants of cereal on their trays, the students chatted noisily, waiting for their signal to disperse.

When the prompt came, it was barely audible. In less than three seconds, the school bell’s muted tone subtly triggered the more than 500 students to head for class.

For Principal Steven Bailey, who recently changed schools, something once as simple as the school bell became a challenge last year. After realizing that loud and unexpected noises were upsetting to some of the school’s 78 “newcomers,” he tinkered with the bell to make it less jarring.

In the Cajon Valley Union School District, where Emerald is located, more than 880 newcomers — students born outside of the U.S. and who have never attended an American school — enrolled during the 2016-17 school year. Many of them arrived as refugees, settling in this San Diego suburb on the final leg of a journey marked by upheavals.

The district, which serves nearly 17,000 students, is made up of only elementary and middle schools. According to district estimates, about one out of every five Cajon Valley students came to the U.S. as a refugee.

For Bailey and the staff at Emerald, last year’s record influx of newcomers created a steep learning curve.

They responded, he said, with shared sacrifice.

The school, which serves grades six through eight, began the year with one newcomer class. By April, there were four. Classes for newcomers ranged from 14 to 24 students. Elsewhere in the school, classes peaked to 36.

“You can either do it the easy way or the right way,” Bailey said. “It’s all about the needs of kids, not adults.”

Nearly 10 percent of all U.S. public school students were English language learners in 2014-15, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Locally, more than 20 percent of students were still learning English in San Diego County last year, according to the California Department of Education.

But because federal law prohibits schools from inquiring about a student’s immigration or citizenship status, it is impossible to say exactly how many of those students have a refugee background.

Still, experts say that schools like Emerald must recognize — and respond to — the difference between refugees and other newcomer students.

Compared to their immigrant peers, refugee students are more likely to have gaps in their education and less likely to be literate in their native language. Research also shows that refugee students have higher rates of mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, which can inhibit their ability to learn.

When anti-outsider rhetoric permeated the nation’s airwaves during the 2016 presidential campaign, Cajon Valley doubled down on its embrace of refugees, holding private meetings with new families and sponsoring classes for parents, district officials said. To meet students’ needs, the central office invested in four counselors devoted to working with children affected by trauma.

“We understand that it’s not just about academics,” said Aber Maayah, who coordinates refugee services for the district. “We really have to look at our kids as a whole. We need to make sure that their social and emotional well-being is in consideration.”

Juggling dollars to educate refugees

According to the California Budget and Policy Center, the state spends approximately $10,000 on each of its K-12 public school students per year. But because state funding is based on average daily attendance, the later a student enrolls in school, the less funding a district will receive.

In the Cajon Valley district, the first day of school for many refugee students often comes midyear. And for a district where more than 70 percent of its students come from low-income households, a steady trickle of newcomers can exacerbate an already difficult situation: how to serve more high-needs kids with fewer resources.

Cajon Valley says it crafts its budget to anticipate additional costs each year — a lesson learned after years of enrolling newcomer students long after the start of school. To fill any gaps, the district has looked for other revenue sources, officials said.

Last school year, 220 of Cajon Valley’s refugee students got a boost of support through an after-school program funded with federal grant money. Students received extra English language instruction and counseling services. They were also exposed to different enrichment activities, including soccer and photography, Maayah said.

But the federal government changed the way it administers the grant in 2016, resulting in fewer dollars for Cajon Valley students than in years past. After-school programming had to be shortened from three to two days, and a month-long summer program was canceled.

District officials say they’ve plowed ahead in search of solutions.

In December, staff traveled to Dearborn, Michigan, another city with a significant refugee population. There, they toured classrooms and learned about the school district’s efforts to serve its refugee students.

A few months later, Cajon Valley school officials lobbied state lawmakers in Sacramento for more funding. In June, legislators approved a one-time budget deal to distribute $10 million among districts with high proportions of refugee students.

With one of the largest refugee student populations in the state, Cajon Valley schools will get a significant piece of that funding.

Finding the right teachers

Eleven newcomer teachers were employed across Cajon Valley schools last year, according to Eyal Bergman, head of the district’s family and community outreach. Of those, six were hired after the school year started and in response to a wave of new students, he said.

“They get to know students. They get to understand them. They get to calm their anxieties and their fears,” Bergman said.

One of those teachers is David Olsen, who was hired in January after Emerald began taking overflow enrollment from a neighboring school. Among the school’s new students were several refugees.

Before coming to the U.S., many of Olsen’s students spent time in Jordan or Turkey, where they say they didn’t feel welcomed. One of his students was shot, he said. Another’s mom was killed by ISIS.

Once in the U.S., news reports about travel bans caused students to worry whether friends and family members back home would get out safely, Olsen said. One morning in the spring, a male student confided in Olsen that he had just learned a friend had died while trying to escape Iraq.

All students at Emerald have access to a counselor, but for those who have experienced significant trauma, the school relies on partnerships with community-based organizations, including the Crossroads Family Center in El Cajon.

Olsen, a former elementary teacher, said his students benefit from the stability of being with one teacher throughout the day. His approach to teaching has also been influenced by what his students have endured, he said.

“For some of the students who haven’t been able to go to school, who have missed school because of being a refugee, I want to give them maybe a little piece of their childhood that they missed,” said Olsen, who gives his adolescent students recess, read-alouds and carpet-time.

Last spring, many in the El Cajon community anxiously followed each new development about the Trump administration’s travel ban. At Emerald, wary students and staff tried to remain positive.

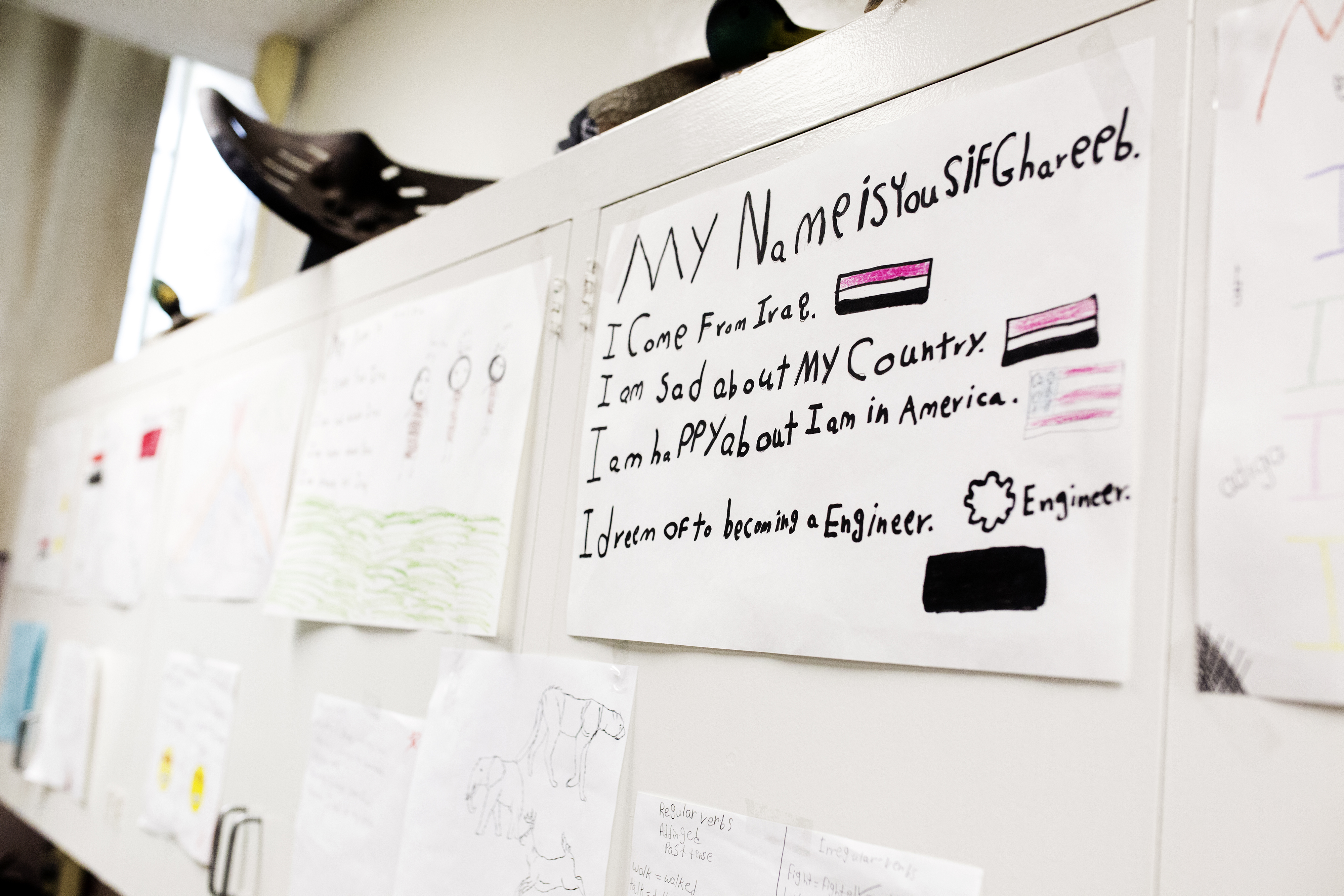

In Olsen’s classroom, boys and girls sat together in small groups — an adjustment for some students who had only attended single-sex schools. They giggled with each other and raised their hands to ask for help. Behind them, their art hung on the classroom wall.

“I come from Syria. I am sad about my country. I am happy about school,” read the rainbow-colored letters of one student’s work.

Bailey, the school’s former principal, is appreciative of his role.

“Every student and family that I talk to, they plan on staying here and becoming citizens of this country,” he said. “They want the American dream.”

San Diego Unified School District: ‘It’s the entire community looking after these kids.’

On Tamba Fallah’s first day at San Diego’s Crawford High School in 2009, the 15-year-old Liberian native was very confused.

What were his new teachers saying?

Where was he supposed to go for lunch?

How would he ask to use the restroom?

And then, there was the worst possible scenario for the teenager who had just arrived to the U.S. as a refugee: What if he embarrassed himself in front of his new American classmates?

Luckily, Fallah said, he soon discovered he wasn’t alone. His peers — some refugees, others immigrants — were also new to the U.S.

They would learn English together.

“That pumped me up and pushed me forward to learn,” he said, recalling his time in a class just for newcomers.

It would take Fallah a year before he was ready to enroll in classes with his American-born peers. But when he finally did, he had the English skills and the confidence to succeed, Fallah said. In 2014, he donned a blue cap and gown and walked across the stage to receive his high school diploma.

The newcomer class teachers “built me up from scratch,” said Fallah, who now works for the state maintaining parks and nature trails and has taken courses at a community college in auto repair. “I don’t think I would be where I’m at today without them being in my life.”

But Fallah, who has since called those teachers for help with his college coursework, is worried that new immigrant and refugee students at Crawford won’t have the same support. That’s because the San Diego Unified School District shuttered its newcomer program — including the Crawford class — at the end of the 2015-2016 school year.

San Diego Unified said it wants to provide newcomer students with greater access to a college-prep curriculum. Beginning last school year, new immigrant and refugee students started spending portions of the day in classes with non-newcomer peers, putting them on a faster track to earn the credits necessary to graduate.

Advocates for the refugee community have criticized the change, faulting district officials for having unrealistic expectations for students with gaps in their education. How can refugee students succeed in high school-level classes, critics have questioned, when they can’t read or write in their native language, let alone English?

“This is not just your basic kid who has some special need,” said Kris Larsen, a former newcomer teacher who protested the policy change before retiring in 2016. “It’s a different kind of special need.”

Going in a new direction

Under the old program, high school-aged newcomer students spent up to a year in a specialized program, remaining with a certified English language teacher for most of the day and joining their peers for electives, such as physical education. Now, newcomers take one period of English language instruction that is taught by a teacher and a language “coach.” That same coach then follows students to core classes, including math, for additional support.

Sandra Cephas, director of the district’s Office of Language Acquisition, said the new model has made the success of newcomer students a schoolwide responsibility.

“It’s not just the English language teacher anymore. It’s the entire community looking after these kids,” Cephas said.

But according to interviews with multiple San Diego Unified teachers, the district’s vision is failing.

Six teachers interviewed for this story expressed concerns over the new program, having witnessed the effects of the change this past school year. Some newcomer teachers said they were not trained or given time to plan with language coaches. At the middle and high school levels, students are scattered across complicated schedules, making it impossible for coaches to support every child, the teachers said. Some teachers said they didn’t have access to translators when they needed to get ahold of a struggling student’s parent, while others said there was pressure to give kids passing grades in core content classes.

As the district finished the first year of the changed newcomer program, school officials were faced with a $124 million budget shortfall, which forced them to issue layoff notices to nearly 1,000 employees at the end of the 2016-2017 school year.

San Diego Refugee Numbers Shrink

Half of those jobs were reinstated over the summer, but the tumult has caused anxiety for many teachers who remain, including those interviewed for this story. Five are still employed by the district and have asked for anonymity out of concern for their jobs.

Larsen, who taught newcomers at San Diego High School, said part of the problem is that district officials made decisions far removed from where it matters most: the classroom.

“For this being San Diego, a city of immigrants and a city of refugees, the district should have gotten it’s act together,” Larsen said. “We should be leading the way. And we’re not.”

Policy experts say that whatever approach school districts choose, educating high school-aged newcomers is especially challenging. And for refugees whose life experiences have resulted in years of missed schooling, the task is even tougher.

“They have the farthest to go and the least amount of time to get there,” said Julie Sugarman, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

Because high school completion is credit-based, refugees start in the ninth grade regardless of their age or educational background. In San Diego Unified, students need 44 credits to earn a diploma. Most classes are worth two credits each.

Statewide, nearly 70 percent of English language learners in the class of 2015 graduated on time, according to the California Department of Education.

However, in San Diego Unified, which has one of the largest proportions of refugee students in the state, graduation rates have not been as strong, Cephas said.

During the 2015-2016 school year, San Diego Unified conducted an internal review of its graduation rates. According to the district, half of all newcomer students at some schools were failing to graduate within four years. The district would not provide specific data on this.

San Diego Unified changed its approach to educating immigrant and refugee students last year to try to improve those figures, said Cephas, who oversees the district’s English learner instruction.

“We don’t have to wait for them to learn spoken English before we can introduce content knowledge and language. It can be done simultaneously,” she said, noting that the state adopted new learning standards for English language learners in 2012.

Under those standards, schools must provide English language learners with meaningful access to grade-level content while also developing their language proficiency.

In San Diego Unified, immigrant and refugee high school students are now placed immediately into an integrated math class where they can earn credits toward a high school diploma. After initial pushback from teachers and the community, the district also began offering a remedial math class for newcomers with significant gaps in their education.

According to the district’s data, 54 percent of newcomer high school students who were enrolled in a regular math class long enough to receive a grade during the spring 2017 semester passed with a C or better. All students enrolled in remedial math, however, passed with a C or better.

Advocates for the refugee community remain skeptical.

Daniel Nyamangah, who works with students at Crawford High School through the nonprofit Social Advocates for Youth San Diego, worries that refugee students, in particular, are being left behind in the rush to graduation.

Instead of going to classes where they feel overwhelmed and unsupported, some refugee students have begun hiding in bathrooms or staying home from school altogether, Nyamangah said.

For Crawford’s approximately 72 newcomer students last year, there was just one language coach, Cephas said.

“A 15-year-old in 10th grade who does not speak English, does not know how to construct a sentence in English — if they are forced into mainstream classes before they are ready, what do you think they’ll do? They’ll just try to drop out,” Nyamangah said.

Advocates warn that increased truancy rates among newcomer students could have long-term consequences for the wider community. For many refugee parents struggling to find work in San Diego, the path to upward mobility often begins with their children’s success at school, said Larsen, the retired newcomer teacher.

Without that success, families could be forced “further into deep poverty that they can never climb their way out of,” she said.

Cephas, who has worked for San Diego Unified for more than 20 years, said the district recognizes the need to improve its support for refugee students but that “slowing down the curriculum … is not the answer.”

For its oldest newcomers, the district is working with San Diego Continuing Education and the San Diego Community College District to develop alternative pathways to graduation, Cephas said, and the district also plans to work with community-based organizations to improve its translation and counseling services.

“Many of our refugee students have gaps, but they also have strengths,” said Cephas, who hopes future graduates will return to San Diego Unified as part-time translators or mentors.

“They come with grit, with resilience. They come with motivation. And that’s what we want to be able to capitalize on,” she said.

City Heights Prep Charter School: ‘Beginning to end, it’s grassroots.’

Merdin Mohammed roamed her eastern City Heights neighborhood one afternoon in late June, knocking on doors and chatting on sidewalks. Armed with enrollment paperwork and a smartphone translation app, the outreach director for City Heights Prep Charter School had a mission: find more students.

The school, which opened in 2012, has grown by one grade-level each year. When it welcomes students back today, the charter will have its first 11th grade class. And if its door-to-door recruitment efforts pay off, the school hopes to expand ever further.

According to the school’s director, Marnie Nair, it’s not just recruiting tactics that set City Heights Prep apart. She estimates that about two-thirds of the charter school’s approximately 160 students are currently or once were newcomers to the U.S., either as immigrants or refugees. All together, the school’s students speak more than 25 different languages.

Charter schools — funded with taxpayer dollars but managed by private organizations — have long been lauded by school choice advocates for their ability to offer innovative alternatives to traditional public schools.

Beyond San Diego, charters have cropped up to serve the needs of refugee students from Chicago to suburban Atlanta. And with a proposed $400 million investment in charter school funding from the Trump administration, more schools with similar missions could be on the horizon.

At City Heights Prep, students attend classes in a five-story building leased from a local church, a lone tower in the residential neighborhood’s skyline.

As a charter school, City Heights Prep can enroll students from anywhere in California. But because of the school’s close proximity to apartment buildings used widely for refugee resettlement, most students walk there from the surrounding neighborhood.

Clad in uniforms of light-blue polo shirts and navy slacks, all of the school’s students come from low-income households, Nair said.

Last year, the San Diego Unified School District renewed the school’s charter for five more years, based in large part on students’ academic gains, Nair said.

During the 2014-’15 school year, students demonstrated above average growth in both reading and math, according to standardized test data. Data also showed that the longer English language learners remained at the school, the greater their scores improved each year.

Refugee and immigrant students at City Heights Prep have one hour of English language instruction each day but are otherwise with their peers. The school’s newcomers represent a diverse array of language backgrounds — from Portuguese to Pashtu — and are quickly motivated to use English as a common language, Nair said.

Making charter school work for refugees

Nair, who lives near the school, decided to open City Heights Prep in 2009 after community discussions revealed that parents wanted more educational options for their children. Three years later, after a series of public hearings and authorization of the school’s charter by San Diego Unified, City Heights Prep opened with just one sixth-grade class.

The first challenge, Nair said, was filling classroom seats.

“The first year the school opened I would be driving along and I would be like, ‘That kid looks like he’s in sixth grade,’” Nair said, recalling her early efforts to find students.

In San Diego, resettlement agencies are responsible for ensuring refugee children enroll in school. But because agencies typically bring families to enroll at district schools, Nair has had to rely on word-of-mouth endorsements among refugee parents.

“We know a lot of the families in the community,” said Nair, whose staff members attend community events regularly and can now spot when there are new faces among the crowd.

“Beginning to end, it’s grassroots,” she said.

Starting the 2018-2019 school year, City Heights Prep will have its first senior class, and Nair expects to enroll more teenage newcomers as the school expands.

The charter school is designed to serve students even after they turn 18 if they need more time to earn a high school diploma, Nair said. Under California law, students can remain in school until they turn 21, but they must be continuously enrolled in the same school in order to do so.

“That’s one of the great things about being a small school,” she said. “We can be very responsive to our students’ needs.”

But the school’s small size has also posed challenges.

In recent years, handfuls of students have transferred to larger district schools, especially for high school grades. Students who leave are often interested in joining sports teams or being in classes with neighborhood friends. Others, Nair said, just want to go to a school where they think there will be less homework.

“The kids learn English faster than the parents. So in a lot of situations, the kids are making a lot of decisions,” she said.

As the charter becomes more established in the community, more students are choosing to stay from one year to the next, Nair said. At the end of the 2012-2013 school year, 76 percent of the charter’s students re-enrolled. The share of students re-enrolling rose to 84 percent at the end of the 2015-’16 school year, Nair said.

She said City Heights Prep would like to build upon that momentum and eventually expand the school to serve 400 middle and high school students. But with fewer refugees entering the country under the Trump administration, it’s been more difficult for the charter to find those new students, Nair said.

Still, the staff at City Heights Prep says there’s plenty of work to do in serving students already on the attendance rolls.

And for Mohammed, the outreach director tasked with networking among the refugee community, that work is personal. Mohammed’s family came to the U.S. as refugees from Kurdistan, Iraq, when she was a child, and she has lived in City Heights since elementary school.

Last year, nearly 80 percent of the school’s newcomer students were refugees. Each day, Mohammed and her colleagues reminded them that hard work will lead to future opportunities, including higher education.

For many of the students, Mohammed said, dreams of college may have been impossible before finding refuge in the U.S.

“One parent told me that they could tell the school really cares about student success and education because back home — where home was in Syria and Lebanon — the teacher would have his coffee, put his legs up on the desk and smoke a cigarette,” she recalled. “He said, ‘Back home, that was how it was.’”

IRW partnering with KPBS

This story is part of an occasional series about the struggles refugees face when they make San Diego County their home. The project is a collaboration among reporters, photographers, videographers and editors at the Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University and inewsource and KPBS in San Diego. Why this topic? Since 2009, more than 23,000 refugees have settled in the county, more than any other region in California.

Trump’s Travel Ban

In June, the Supreme Court agreed to hear challenges to the Trump administration’s travel ban, which — in addition to banning entry to the U.S. for citizens from six majority-Muslim countries — would bar all refugee resettlement for at least four months.

In its acceptance of the case, the court allowed the refugee blockade to move forward immediately for those without “bona fide” relationships in the U.S.

El Cajon and its refugees

El Cajon, about 15 miles northeast of downtown San Diego, has a well-established refugee community of Iraqi Chaldean Christians that dates back to the 1970s. Markets stocked with Middle Eastern ingredients are plentiful, and Arabic signs dot the main roads.

More recently, refugees from other Middle Eastern countries, including Afghanistan and Syria, have settled in this city of about 100,000.

City Heights is a densely populated neighborhood in central San Diego. It is known for its ethnic and cultural diversity; more than 40 percent of its nearly 70,000 residents were born outside the U.S. Immigrants from East Africa, Vietnam and several other countries have established vibrant communities in City Heights thanks to affordable housing. But in recent years, rent across San Diego has skyrocketed, forcing some families to relocate.